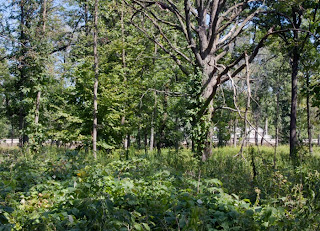

There is a lovely woodland on the west side of Interstate 94

north of Chicago that I’ve driven past innumerable times on my way to and from that

great city and points east or south of it. Its name, or even whether or not it

had one, has always been a mystery—until today.

Since I am the “designated driver” in my family when we are

anywhere near Chicago, I’ve rarely gotten more than a passing glance at this

park as it flashed by at prevailing freeway speeds. But I do glance. Many of

metropolitan Chicago’s patches of forest preserves lie alongside the freeway

corridors. There they are welcome variations in the otherwise dull “viewsheds”

that have in recent years become dominated (or shall we say it bluntly:

obliterated) by the sound-absorbing barriers erected to protect burgeoning

subdivisions.

When the patches of woodland green flash past I invariably

take a glance (or two, road conditions permitting!) Over the years I’ve gotten

to know quite a few of these fleeting bastions of nature. Or, to be more

precise, I’ve become superficially familiar with the face they present to the

freeway. (There’s no “stopping by woods on a snowy evening” along the freeway,

of course.) This particular stretch of woods has seemed especially inviting. On

occasions when the sun’s rays stream through the tree canopy they reveal, even

at freeway speeds, an open understory that can appear quite enchanting. A

gracefully arched footbridge is visible, as it crosses over some watercourse

unknowable from the road.

Welcome as these brief, beguiling glimpses are as visual

distractions on a road trip, they are definitely unsatisfactory to someone who

desires an intimate “acquaintance with nature,” as Thoreau put it. I cannot

recount how often I have yearned to take the next exit and double back to find

this park. That it took so long may be attributed to destination-minded driving,

to the inertial logic of freeway traffic, or to an internalized skepticism

about the chances that roadside parkland can live up to my imagination of it as

urban wilderness.

Today I resist skepticism—and I plan time into my return from an errand in Chicago. I exit the

freeway at Half Day Road and turn north on the ambivalently named Riverwoods

Road Trail. Definitely a road; not a trail. The park is easy to find but the name,

when I finally see it on the entrance sign, is disappointingly prosaic: North Park. No matter: “A rose is a rose is a rose” and, prosaic or not, it will

“smell as sweet,” to mix quotations. And the Shakespeare, referencing smell,

will prove very apt indeed, as we shall see.

I drive past a series of athletic fields, down a very long,

narrow set of parking spaces, every one of them empty today. Not surprising,

though: it’s just after noon on the first day of the new school year. (I’ve

just driven past Daniel Wright Junior High, which has a packed parking lot and

a marquee sign reading, “Welcome back!”) I park at the far end, delighted, as

always, to have the woods to myself. Tempting to throw in the Thoreau quote

about companionable solitude, but I so recently used it, I’ll resist. Besides,

although there is no one else about, as I enter the woods the solitude and

otherwise bucolic character of the woods is immediately and, as it will turn

out, irrevocably compromised by the incessant roar of the beastly freeway;

ironically, the very conduit that led me to this moment of exploration.

It is a small sacrifice, I always think as I embark on a new

urban wilderness adventure, to have to endure the racket in order to enjoy the nature.

Unfortunately, it is one to which I am accustomed. I forge ahead. At first the

forest is dense and shadowy, but soon the understory opens as I had foreseen

from the freeway. A wide, neatly mulched trail makes the trek decidedly tame. But

the sun is pouring through the foliage; it spreads across the dry ground like

butter on toast. I can ignore the noise. The scent of the earth is sufficient,

I think to myself, to transport me away from the Interstate, away from

Illinois, into that enchanted place that I have been imagining here all these

years.

The air is sultry. The leaves, still vibrantly green,

haven’t begun to turn. And yet the dry, earthy scent no longer speaks of

summer. It is an autumn scent, redolent of finality. But it is the finality of

transformation, of new beginnings as well as endings. Summer, the season of

indolent days and endless youth, is over. Autumn may presage winter, but begins

with a new school year full of hopes and promises. This is the finality of cyclical

nature, not the finality of death. For, unlike we mortals who walk in its

paths, nature never dies.

Unless it is paved over.

OK, OK: sorry. I had to do it. I was getting a little

maudlin there, with the syrupy sentiments. The trucks are still roaring by on

the Interstate. I’m trying to ignore them, but there they are, RIGHT THERE. The

trail I am walking angles towards the freeway and the scrim of trees is

tapering. The traffic, no longer merely audible, is a clearly visible blur. I

can now make out brand names on the trucks—and super-graphics of fresh

vegetables on their way to the shelves of some supermarket.

It is true that nature never dies. Nature will outlast us.

Paradoxically, perhaps, it’s also true that we’ve been killing it little by

little for at least a couple thousand years, but lately at a rapidly

accelerating pace. A freeway through here, a new subdivision there, a little

more carbon in the atmosphere, another 200,000 people added to the planet since

yesterday.

Well, yes, it is all of a piece: a new year; hopes,

promises, youthful vigor and ambition—these things come burdened with death and

decay, violence in the Mideast, global warming, and so on. A walk in these

woods comes with the roar of trucks on the Interstate. One ball of wax. Yin and

yang. Urban wilderness. Every little—and big—thing “hitched to everything else

in the universe.” Forever and ever, Amen.

I’m still walking through the lovely woods, breathing the

sultry air, basking in the buttery sunlight, stopping to delight in the glow of

asters and goldenrod. It’s still beautiful. I come to a sign, posted knee high,

encased in watertight acrylic, and canted for easy viewing. “We all live in a

watershed,” it proclaims to those who pass.

I approve, of course. Having written Urban Wilderness about a watershed, I’m all for educating the

public about the importance of drainages, aquifers, wetlands and rivers; of

understanding natural geography—biodiversity, ecosystems and watersheds—instead

of the imposed geography of cities, streets, counties and freeways. “North Park

was designed to protect the natural area and watershed of the Chicago River,”

it says. Then it asks, “What can we do to protect the watershed?” And, appropriately,

goes on to provide a detailed list of answers.

Halfway down the list I read, “Preserve our open spaces.”

Indeed, I think ruefully, as a truck RIGHT THERE on the freeway throttles down,

engine groaning. “Restoration of the natural area here at North Park will

improve water quality and reduce flooding along the Chicago River.” Yes, it

will. In a curious bit of graphic invention, the map on the sign shows the

Village of Lincolnshire as an unnaturally spiky purple blotch that appears

attached to the side of the smooth green shape of the watershed like a parasite

or a cancerous growth. North Park is a tiny blue shape shoehorned between

Lincolnshire and Interstate 94. Three long forks of the North Branch of the

Chicago River extend down and away from this point at one of the headwaters.

What is missing, however, are all the adjacent, equally

irregular and obtrusive shapes of towns and villages like Lincolnshire here in

Lake County, Illinois that overlay the entire watershed. Lake County is home to

over 700,000 residents. They all live in a watershed. Unless they choose to

walk this trail in North Park and to stop to read this sign, I wonder, how

would they know that?

I reflect on the word watershed, which has another, related, meaning. If I walk west from North Park to the far side of Lincolnshire, at some invisible point I will cross from the Chicago River drainage to where all the rainwater flows into the Des Plaines River instead. Temporally, too, the tipping point when everything changes is often referred to as a “watershed moment.”

Not long ago we were warned that once carbon levels in the

atmosphere reached 350 parts per million (ppm) there would be no stopping the

disastrous effects of global warming. Today, as CO2 levels approach

400 ppm some organizations, businesses and countries are scrambling to reverse

the trend and re-cross the watershed.

This week there were news reports that a long-awaited

turnaround has sent home prices soaring again. A watershed. Good news, of

course, for the many people still caught in financial straits brought on by the

Great Recession. Rising home prices, however, also means rising prices on land

and a resurgent demand for development. According to the New York Times, “The

latest land rush is in full swing, as developers realize that they have failed

to feed the zoning, permitting and mapping pipeline, which can take months or

years to turn raw fields into buildable lots.” Municipalities are adjusting

rules, lowering development fees, and using other strategies designed to

encourage this new “land rush.”

We all live in a watershed.

The warm, autumn scented wood is dappled with sunlight. The flowers are dazzling. I

reach the gracefully arched footbridge I’d glimpsed so many times through the

trees from the freeway. A faint trickle of water sparkles here and there

amongst lush wetland reeds and grasses. Meager headwaters of the West Fork of

the North Branch of the Chicago River in an obscure little woodland squeezed

between Riverwoods Road Trail and Interstate 94. Never more important than

today, right now in the watershed.

I've always noticed that woodland, too. Thanks for sharing a bit about it. I hope to wander around in it someday, too.

ReplyDelete